I recently read a novel that paints an eerie prophecy of the “organized destruction” tactics we are witnessing today. This piece of classic literature has been proven true once before; a hundred years ago by the very people that the author was originally trying to warn- his beloved Russia.

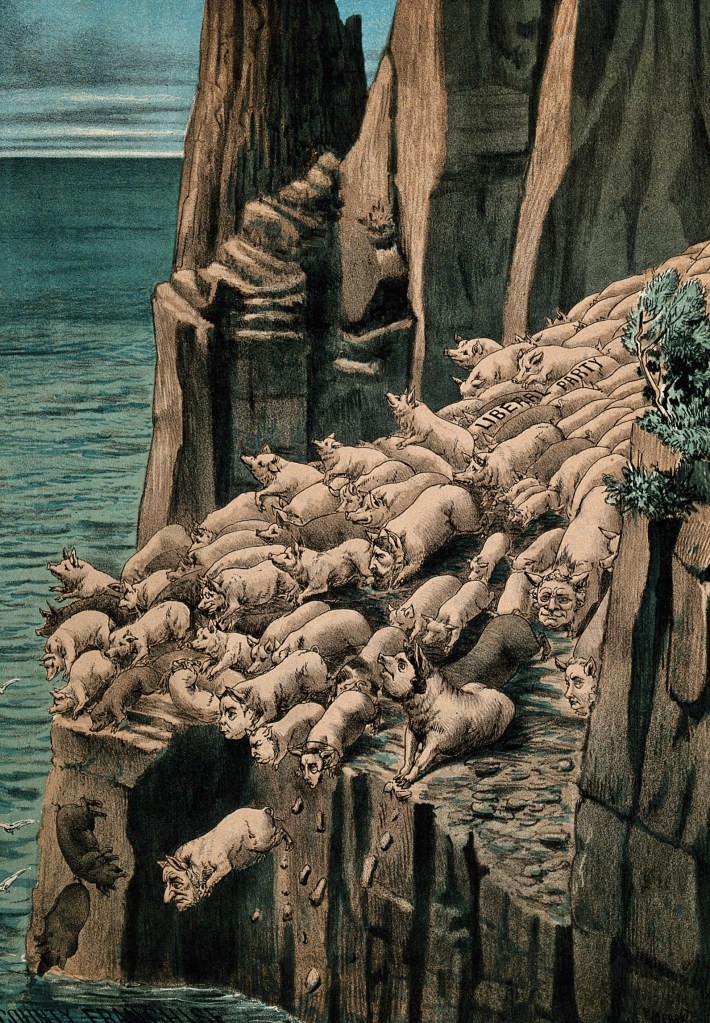

Now I don’t pretend to understand all of the implications of this work. Out of the Dostoversky I’ve read I found this to be the hardest to grapple with. The book is named after the Biblical story in Luke 8, where Jesus casts out the legion of demons from the man possessed, the devils then rush into a herd of pigs and are drowned. It’s set in a small provincial town in 1860’s Russia, and like all Dostoevsky’s novels, allows us to see big ideas played out in a small microcosm.

Here are four prophetic archetypes that I want to mention:

The first is in the person of Stepan Verkhovensky. Now he–Stepan for short–is the father of the main radical rabble rouser, Pyotr Verkhovensky, as well as the teacher of Nikolai Stavrogin, the smart, idle, and twisted son of the wealthy Varvara Petrovna. Stepan is something of a buffoon representing a generation of moral weakness, toying with the nihilistic ideologies that later his son and his student will take to their logical termination. He denounces any belief in God, yet at any crisis he’s always praying. He makes little speeches using the jargon of the radicals to appear hip to the younger generation (who all look down on him) without really grasping where those ideas will lead. He’s under the patronage of Varvara Petrovna (the wealthy mother of Stepan’s student Nikolai) who believes–for the first half of the book–that Stepan will help change the world for the better. By the end she realizes that he’s only an empty shell. Yet that empty shell was the stepping stone for truly villainous men and their devilish viewpoints.

The second is Nikolai Stavrogin, the son of Varvara Petrovna, and in his youth, the pupil of Stepan. He takes the radical ideas to heart though not in a political way–much to the exasperation of Pyotr Verkhovensky (Stepan’s son) who longs to set Nikolai up as the figurehead of a Revolution–but to satisfy his own deep sensuality. And he is warped. Shatov, one of the few good characters, at one point had hoped that Nikolai would be a voice to call Russia back to its Orthedox Christain roots because he believed Nikolai had great potential as a leader. Later, when he became better acquainted with his blackened heart Shatov said of him that he was driven by “a passion for inflicting torment”, not merely for the pleasure of harming others, but to torment his own conscience and wallow in the sensation of “moral carnality.” He raped a girl and watched with listless pleasure as she destroyed herself. A sweet but mentaly insane girl comes into his path and he marries her for the sake of torturing her. Nikolai once confessed to a priest that; “I neither know nor feel good and evil and I have not only lost any sense of it, but there is neither good nor evil… and it is just a prejudice.” He’s very handsome, refined, brave, and bored with his meaningless existence, so he tries to find power through committing the worst possible crimes. Indeed, the only spark of humanness about him is that he commits suicide at the end of the book.

Thirdly is Pyotr Verkhovensky. Now Pyotr’s father, Stepan (see first guy), was absent for most of his life. When Pyotr returns to the town Stepan is eager to be close to his son. Pyotr however, is disgusted with his father. Dostoevsky’s brilliant connection of the 1840’s liberal idealist to the nihilistic revolutionaries of the 1860’s are shown through this pair; the father playing with the demons that the son would become possessed by. Pyotr was a fantastic manipulator. He knew how to flatter and how to lie, skills which he used to the best of his advantage. His plan was simple; cause mayhem and scandals to break out all over the town “for the systematic shaking of the foundations… of society… in order to dishearten everyone” and then when the citizens were “ailing, limp, cynical and unbelieving” yet longing for “some guiding idea and for self-preservation” make his move and raise “the banner of rebellion.” To that end Pyotr organized a small group of men, promising that there were thousands of such secret organizations all over Russia. He stirred up a workers revolt from the men in a certain factory, started a fire, made a fancy ball turn south, and helped cause several murders. Pyotr also convinced his group that Shatov, the character that wanted Nikolai (see guy two) to lead the country back to God, had information and would turn the group over to the police, thus putting the whole “sacred cause” in jeopardy. So they consented–most of them against their better judgment–and murdered Shatov. It proved too much for the group and they crumbled. One of the members was driven by regret and confessed the whole plot to the authorities. Pyotr somehow caught wind, and fled the country.

Fourthly we have Julia von Lembke. She’s the ambitious wife of the new governor, and the unconscious dupe of Pyotr Verkhovensky (see guy 3). She longs to make a difference in the world; to fight for social justice, setting herself up as the hero of the hour. She believes in the flattery that Pyotr is constantly whispering into her susceptible ear. He convinces her that he’s on her side; while behind her back using the support he gets from her to his own nefarious ends.

If those four characters don’t bring to your mind what is wrong with America today, you aren’t paying attention to our current cultural situation.

We’ve had a few generations of Stepans; men who think they’re “liberal” and play the fool. They’re gullible to whatever the latest fad from their party is, without recognizing the true implications of those ideas.

We also have our fair share of Nikolais. They are powerful, educated, and grossly perverse. I “know neither good nor evil” and “it’s all just a prejudice” could be their motto. Without anything higher to live for they turn to debasing themselves in evil for evil’s sake. Enough said here.

Pyotr is the radical left. Snaking their way into the hearts of men by finding a weak spot and exploiting it. He would fit right into the BLM leadership, Antifa would be a dream to him, and he’d know how to use Covid-19 to his advantage, causing societal breakdown to make the average citizen ready to believe his narrative, thus enabling him to usher in things like communism and socialism or whatever he and his little group stood for. I think this is the core message of the book. It’s a warning, don’t buy Pyotr’s story; it will destroy your town and lead to rack and ruin.

And lastly poor Julia von Lembke, like many today who buy, at least in part, the left’s agenda and are blinded by claims like “this is to abolish racism” or “let’s shut down the economy, it’s for your safety”. She didn’t want the destruction of society, she only wanted to help. She thought that groups like Pyotr’s were there to bring “social justice”. But she was in for a rude awakening.

There is of course a lot more to this great book. It’s over 700 hundred pages, very dark, and at times confusing. I still am not sure who the main character is, if there even is one. There’s other characters, twists, and side plots galore (Russian literature for you). But at the heart of the book is this prophetic warning; beware of those demons in your midst; before you all run headlong off a cliff.

Dostoevsky had seen the handwriting on the wall; he did his best in this book to let Russia see what was beginning to take place in their midst. Less than forty years after his death, Russia took the plunge “violently down the steep place into the lake and drowned” (Luke 8:33) in the Russian Revolution of 1917. Will we heed the warning, here in America before it’s too late?

You’ve so convinced me to read his books, Alex. They sound really interesting.

LikeLiked by 3 people

You have written a way for us to see ourselves through both the lens of literature and history. Literature gives us the insight to see ourselves and history the outcomes. God have mercy!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and Solzhenitsyn have been a huge part of my life the last 2 years. Trying to figure out the world since Covid is concerning to say it nicely, but also fascinating. Really awakening and learning what human behavior has been capable of and still is, is crucial to our free world.

LikeLiked by 1 person